Whilst writing my latest novel, Lake of Echoes, I took inspiration from a magazine article I wrote several years ago about the annual blood peach festival of Soucieu-en-Jarrest. This festival features in Chapter 24 of the book.

A Tale of the Flesh

By Liza Perrat

A wide banner yawns into the soughing air.

You are cordially invited to our blood peach fair.

You are cordially invited to our blood peach fair.

Sunday September 8. Discover the blood peach in all its guises in Soucieu–en-Jarrest, where the Romans once roamed.

22 kilometers west of Lyon, home to reputed wines, fruit and vegetables, the village of Soucieu–en–Jarrest nestles in a valley of the Coteaux du Lyonnais (Lyonnaise hills), minding its own business. And on the first Sunday of every September its business is the blood peach.

“So what’s the big deal about peaches?” I ask a local farmer.

“Not just a peach, Madame,” he answers, as if I have personally insulted him. “Our Eastern-born, flavourful fruit with flesh the color of blood. Traditionally blood peaches grew next to the vineyards,” he explains. “They were easy to grow and susceptible to many of the same diseases as the local vines. But the signs of disease are quicker to develop and more obvious on peach trees than on the vines. So, violà, the vine growers would plant peach trees next to their vineyards to warn them of potential problems.”

So, with its questionable history as martyr for the cause, I ask myself if the humble blood peach can now hold its head high as a separate identity?

As Soucieu-en-Jarrest’s 3,000 or so inhabitants and a wealth of fair visitors loudly proclaim its independence, I am certain that the blood peach does retain its place in the arboricultural patrimony of the Coteaux Du Lyonnais, as it has done since the XV11 century.

An explosion of pink geraniums, a sign advertising soupe aux choux and the ruins of the fortified enclosure lost in the revolution announce the village entrance. Fearing a revolution of the intestinal kind, I decline the cabbage soup and head straight for the fruit.

Like a beagle hot on a rabbit trail, my nose takes me to the freshly-baked chaussons, or stewed blood peach slippers, commonly called turnovers. Golden pastries are lined up like, er … slippers, in a dormitory.

“They’re so easy to make,” Marie, the stall holder tells me, aligning her jars of blood peach jam. “Just spread the stewed fruit over the pastry, fold it in half and pop it in the oven for twenty minutes.”

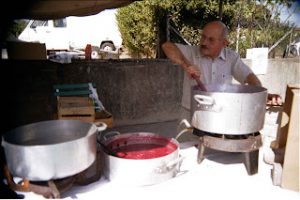

Alongside the turnovers, an elderly man toils over an army-sized steel pot of stewing peaches. His wife breaks up fruit, throwing it into the bubbling magenta mélange. Flicking away stray hair strands, she streaks her face pink and soon resembles an ancient warrior swathed in war paint.

“Stewed peaches take 30 to 45 minutes to cook. For jam it’s one hour,” she informs me.

“And don’t peel the fruit for stewing or for jam,” she warns, waving her wooden spoon threateningly in my direction.

To avoid being crushed like the local wine grapes, I dodge a purple clown on stilts. In his ungainly wake, a troop of majorettes files past. I skip out of the firing line of thrashing pink and green pom-poms and take cover in the stall selling crates of blood peaches, nectar and wine.

A wine maker offers me a glass of white. “You can smell the peaches and apples, n’est-ce pas, Madame?”

“Mmn, delicious,” I say with a nod, savouring the intense, yet charming aroma.

“If Madame would care to try the red too? An exquisite blend of blackberry, blackcurrant and raspberry,” he tells me.

“Sure,” I answer, thinking, and why not the rosé too, while I’m at it?

Finally, nicely mellowed, I thank him and begrudgingly leave Monsieur to his more serious buyers.

“One crate of blood peaches please,” I say to the farmer, whose white apron looks like a

kindergarten finger-painting masterpiece. He hands me a crate, the rounded fruit sticking up like rows of pink baby’s bottoms. “That’s five Euros, Madame.”

Juggling my crate on one arm and slurping a creamy double blood peach sorbet cone in the other, the anonymous voice behind the loudspeaker interrupts the rural conviviality, announcing the folkloric dance group.

Meandering over to the ancient stone front of the Town Hall, I see the Groupe Folklorique de Thurins, a neighbouring commune, is already swinging. Traditional red and yellow skirts flounce as their black lederhosen–clad partners whirl them around the wooden stage.

Sitting cross-legged, the children are unusually quiet. Blood peach ice cream dribbles down their chins, onto their T-shirts and, captivated by the dancers, they nearly miss the start of storytime. We herd the children into the Soucieu library, where a storyteller dressed in a toga recounts a tale of Roman intrigue.

“In forty-three BC, Lyon was the capital of Gaul. It was called Lugdunum and stayed this way for three centuries. The Romans got their water from four aqueducts. These canals were over two hundred kilometers long.” The whites of young eyes flash in the darkened room and the children listen in awed silence as the storyteller unfolds her tale of stolen jewels, culminating in a bloody sword duel atop an aqueduct tower.

Threading through Soucieu-en-Jarrest, the Garon river still bears evidence of Roman presence in the area. The pillars of the Gier Roman and other Gallo-Roman aqueduct ruins tower the forested Garon valley.

Mildly frightened and unaccustomed to the sunlight, the children emerge from the storytelling rubbing their eyes. As well as telling tales, the Soucieu library has organized a taste contest. Blindfolded in turn, the children must identify each of Soucieu’s produce – summer’s tart apricots, raspberries, strawberries, gooseberries and blackberries. The dark pink juice of May’s cherries rolls down their chins and winter pears and apples are crisp.

They become noticeably less enthusiastic when they reach the vegetables – the bright greens and reds of July and August – zucchini, beans, lettuces and tomatoes, then winter’s cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, broccoli, endives and pumpkin.

The setting sun burns the sky the pink and orange hues of surfer’s swimsuits and the background fair music hovers between classical, jazz, modern and occasionally, the indefinable. Tastes of the whole family are accommodated as it is essentially a family day, with something for everyone.

Strategically placed near the bar, some serious competitors are engaged in a pétanque match. The French take this bowling game as seriously as their wine, precisely measuring questionable distances. Soaking up the last of the summer sun, I sip my tangy blood peach cocktail and watch them exclaiming and waving their arms as the metal ball lands where it should, or shouldn’t.

But if your palate is aghast at the idea of a day of blood peach by-products, do not despair. Dolls from many walks of life, a basket-weaving artisan’s wares, glass blown objects, dried flower arrangements and local honey are also displayed. But the shiny tractor–type and harvest machines parked at the end of the street will constantly remind you that this truly is an agricultural community.

As I taste the surprisingly pleasant union of sweet and bland of the white cheese drowned in blood peach sauce at La ferme du Marjon stall, Mr. Loudspeaker orders the crowd to gather for the grande finale.

As I taste the surprisingly pleasant union of sweet and bland of the white cheese drowned in blood peach sauce at La ferme du Marjon stall, Mr. Loudspeaker orders the crowd to gather for the grande finale.

“And now ladies and gentlemen, Monsieur and Mademoiselle Blood Peach will be named.” Smiling under their dubious honour, the chosen young couple are loudly applauded, with a few wolf whistles thrown in.

The sun begins its inevitable departure behind the hills and on the cusp of autumn, the crisp air begins to nibble at our bones. Mothers drag sweaters from heavily-laden bags, the party winds down and a playful breeze is heard whispering centuries of farming secrets through Soucieu-en-Jarrest’s orchards and vineyards.

Then, under the benevolent eye of the village mayor, this year’s fair ends with a messy blood peach pie race.