While this phrase might have been wrongly attributed to Queen Marie Antoinette during the French Revolution, she certainly was not high on the popularity stakes!

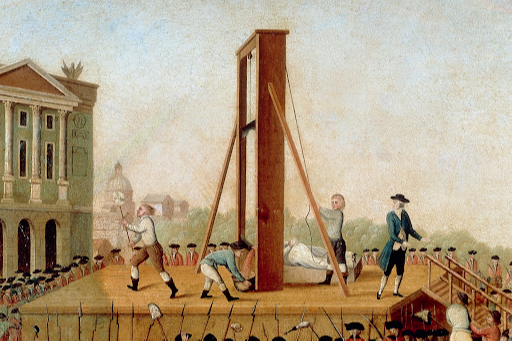

The first important event I wanted to mark was the death of Marie Antoinette on 16th October, 1793. At 12h15, several weeks before her 38th birthday, she was guillotined on the Place de la Révolution (known today as Place de la Concorde).

The second important event took place on October 5th, 1789 and is known as the October March or the Women’s March on Versailles and was one of the first defining events of the French Revolution. It all began as women on the Paris marketplaces protested about the impossibly high price of bread.

This grew into a thousand-strong group of angry and determined Parisians who beseiged the Palace of Versailles. They successfully placed their demands on King Louis XV1 as, the following day, the crowd forced the king and his family to return with them to Paris.

Here is an extract of this event from Chapter 41 of Spirit of Lost Angels…

On that October morning, three months after the fall of the Bastille, an uneasy calm hung over the streets of Paris. It was as if the prison storming had been only the first small wave of discontent, and that some great seism was gathering force, ready to break apart and swamp the entire country.

On that October morning, three months after the fall of the Bastille, an uneasy calm hung over the streets of Paris. It was as if the prison storming had been only the first small wave of discontent, and that some great seism was gathering force, ready to break apart and swamp the entire country.

I had not found Rubie. The words of all the people I spoke to echoed in my head like one continuous drumbeat.

Perished … dead … deceased.

I was almost convinced my daughter hadn’t survived her journey from the orphanage to the wet-nurse. Claudine was right, in the fug of my exhausted brain the night the Bastille burned, I had simply imagined Rubie.

Dawn was quiet and chilly, the little shops still shuttered, as Aurore and I joined my salon friends––Sophie, Olympe and Manon––and the rest of the women marching along the slop-damp cobbles to the low beat of a solitary drum.

When it came light, there were still no coaches or presentable souls about, besides a few clerks hurrying to their offices. All the gardeners though, mounted on their nags, baskets empty as they headed out of town, gaped at the communal stride of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of women.

‘Neither our mayor, Jean-Sylvian Bailly, nor General Lafayette can ensure we have bread!’ Olympe, our self-elected representative, proclaimed to the group who had gathered in front of the Hôtel de Ville. ‘They are withholding bread to crush our spirits!’ She flung an arm in the direction of a bakery shop, and its “No Bread” sign.

‘String them up from the streetlights!’ a woman shouted back.

‘Since the men of our city are unable to put bread on our tables,’ Olympe continued, ‘the women of Paris will march upon Versailles and demand bread.’

‘Let’s go and see the baker, and the baker’s wife!’ a woman shrieked.

A hail of cheers and applause smothered her words, children blew bugles and rang bells, and an even greater knot of women assembled in the Tuileries gardens.

The sky turned dark and cloudy as we marched along the Cours de la Reine with our makeshift weapons: pitchforks, broomsticks, pikes and swords. Six drummers headed our procession, alongside two women riding on cannons. We all boasted the tricolour cockade and carried leafy branches, as we had three months earlier when we took the Bastille.

‘Are we truly going to fire cannons on the palace?’ Aurore said.

‘Of course not,’ I said with a wry smile. ‘We have no powder. They’re only for effect.’

‘What a pity,’ she said. ‘How I would love to see the Austrian whore blown to bits!’

Aurore reminded me of that enraged lioness from Les Barreaux de la Liberté, back arched and tail swishing. ‘However can I calm this hate you carry inside?’ I said.

‘I’ll be calm the day I see the Queen’s head roll,’ Aurore said, striding out ahead as we approached the Barrière des Bonshommes tollhouse.

‘We certainly must fight for what is rightfully ours,’ Olympe said, ‘but like a woman, Aurore, who uses her head, and not like a man, who uses only his stiff cock!’

Laughter and giggles rose from the crowd as we marched on, through steadily falling rain.

Dusk fell and Sophie handed around hunks of cheese and cold meat, and that rain-drenched food seemed the best thing I’d tasted.

Flanked by friends, I couldn’t help feeling imbued with their energy and determination throughout that rainy day, but as we approached the royal palace, my foreboding grew.

‘If slander and malice could kill, blood would flow knee-high in this place,’ I said.

‘With no one spared the treachery and deception, least of all the King and Queen,’ Sophie said, as we plodded on, cold and drenched, down the broad alley leading to the palace.

‘Look, they’ve drawn the gates across the entrance,’ Manon said. ‘They must have had word we were coming.’

‘Good, let the Queen tremble in her golden nightgown,’ Aurore said. ‘Let her shit herself with fear!’

We all laughed––a shivery laugh––as we joined in the chant from the palace gardens: ‘Du pain, du pain, du pain,’a monotonous drone against the cold drizzle.

A group of fifteen chosen women, Olympe amongst them, disappeared into the palace to appear before the King, to voice the grain-hoarding rumours.

When we heard nothing from inside, a band of women, more agitated than the rest, broke off from the crowd. Brandishing their clubs and meat-cleavers, and calling for the blood of the Austrian whore, they stormed into the palace.

‘We’ll fricassee her liver!’ a woman shouted.

‘I’ll make lace out of her bowels!’ Aurore shrieked, joining the angry mob.

‘No, don’t go inside, it’s too dangerous.’ I tried to clutch onto Aurore’s sleeve, but she shrugged my hand off and I could do nothing to stop her belligerent determination.

Musket fire rang out from within. I jumped, a hand over my breast.

‘Please, let Aurore be safe. Let them all be safe.’

‘She’ll be all right. Aurore’s a fighter,’ Sophie said, swiping a hand across her brow and streaking it with dirt. Her dress clinging to her drenched skin, she looked a very different Sophie to the one who received her friends from a milk bath.

We heard more shots, and reeled back in a great human tide as the bloodied bodies of several women were thrown out into the courtyard.

I gagged on my meagre stomach contents, as we picked our way through them, searching the lifeless faces.

‘None of them is Aurore or Olympe,’ Manon said. ‘They’re not here. They must still be inside.’

‘I’d so hoped this could be peaceful,’ I said. ‘That we could voice our concerns in serenity.’

‘Serenity?’ Manon shook her head. ‘No, Rubie, the women are too angry, and starving.’

Everybody joined in the chant for the King to show himself, ‘Le Roi, le Roi!’

The King appeared on the balcony and smiled down on the crowd in the palace courtyard. He promised bread to his loyal subjects, and there rose a cheer of ‘Vive le Roi!’

‘How absurd,’ I said, ‘that we cheer when some of us have already fallen.’

‘La Reine au balcon, la Reine au balcon!’

The Queen stepped onto the balcony in her night-robe. I tried not to smile with the irony as I recalled my childhood dream of meeting a real princess. Marie Antoinette’s face a chalky mask, as if frozen in terror of her people’s hatred, I was certain the poorest peasant girl wouldn’t dream of being this princess.

We all knew Marie Antoinette loathed the Marquis de Lafayette, regarding him as a symbol of the revolution, but the General stood by her side––a liberal aristocrat with the unenviable position of reconciling the mob and the Queen.

‘Shoot the whore!’ a woman cried. People pointed muskets and pikes at her.

For minutes, the air was taut with nervous tension and an expectant kind of silence.

Lafayette remained still, though obviously aware he would be forced to shield the Queen if the people started firing. Then in a dramatic, unprecedented gesture, he turned, took her hand, bowed low and kissed her fingertips.

‘ Vive Lafayette!’ the crowd shouted.

Vive Lafayette!’ the crowd shouted.

For no other reason than perhaps impressed by her bravery in the face of a hated crowd, everyone rose in a collective roar, ‘Vive la Reine!’

Marie Antoinette seemed to fall against Lafayette with relief, before a bodyguard ushered her back inside.

The King agreed to move the royal family from Versailles to Paris, and most of the women began the long trudge home to inform the Parisians of the King’s promises of bread.